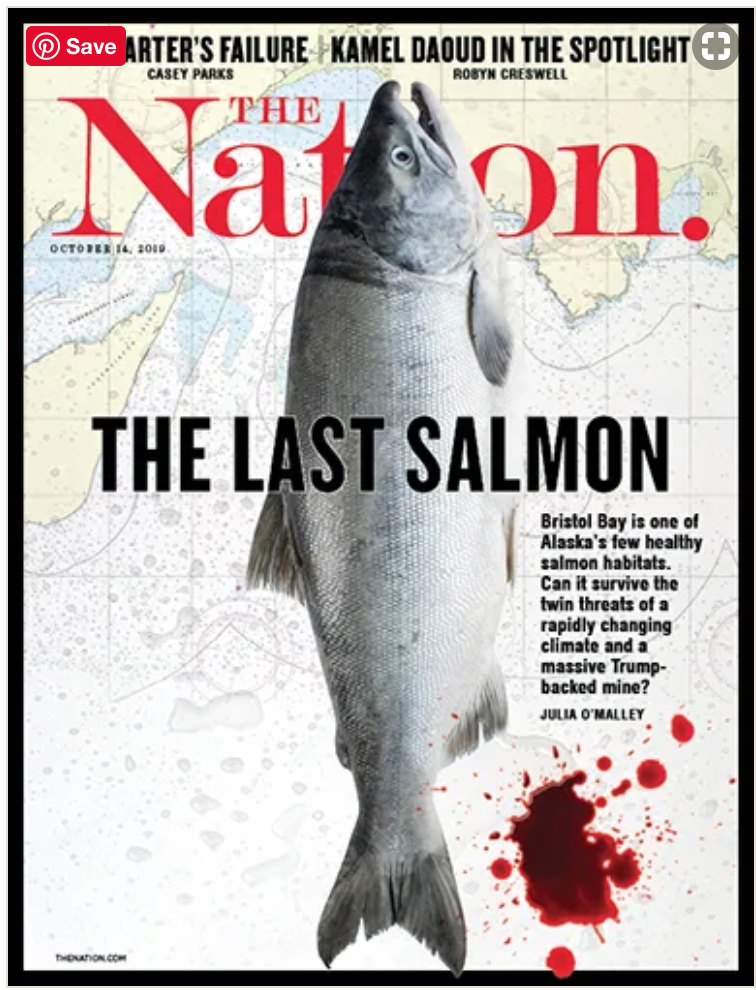

I worked with the talented Nathaniel Wilder to make a cover story about the pressures on Bristol Bay, as told through the experience of Anna Hoover. Last season was her first as captain of her own boat in the world’s most productive red salmon fishery, where most of America’s grocery store fillets come from. It was the hottest summer Alaska had ever seen by many measures. Anxiety over the Pebble Mine proposal, reinvigorated under the Trump administration, ran high.

The story begins like this:

“Coffee Point, Alaska—Anna Hoover and I ease up and down in limestone-colored water on a warm, windless afternoon in early July, our backs to the mouth of the Egegik River. She’s distracted, perched in the captain’s seat of her 32-foot drift boat. She glances at her phone, checking the time. The state manages fishing on a tight schedule here, opening the waters to fishermen and then closing them every few hours to let some salmon travel to their spawning grounds. We’ve got five minutes until we unspool our nets.

We sit 300 miles west of Anchorage in Bristol Bay, home to the largest, healthiest red salmon run on earth, where most wild-grown grocery-store fillets caught in the United States come from. Hoover’s parents and grandparents fished here, and she has been hauling reds from this fertile finger of saltwater for most of her 34 years.

This is her first summer as the captain of her own boat. She never doubted the decision to buy it. She’s always seen herself here, her hair pulled back in a bandanna, rubber coveralls flecked with fish scales, eyes gritty from sleep deprivation, adrenaline rising and falling with the tides that carry salmon into the nets.

“We joke how there are two kinds of people—the ones who can’t stand it out here and the ones who can’t live without it,” she says. “Fishing is in my blood.”

Still, no matter how many years you fish, she says, you always get a crackle of anxiety as you slip your nets into the water. So much can go wrong—weather, gear tangling, mechanical problems, bad timing, the catastrophe of the fish failing to show up. The risk, though, is part of the draw. “Fishermen,” she tells me, “have always been gamblers.”

For her generation of fishermen, investing here is more of a gamble than ever. Twin threats hang over this place where many of America’s salmon dinners come from: a rapidly warming climate, which has already scrambled the pattern of the seasons across vast swaths of Alaska, and Pebble Mine, a proposed open pit mine at the bay’s headwaters, which has been given new life by Donald Trump’s administration. Many who live and fish here, including Hoover, worry that once the mine is built, pollution is inevitable and that together these two forces could destroy this rare, pristine ecosystem, threatening salmon, communities, and whole ways of life.

“I think of generations. So many people in the fishery have learned it from their families and want to pass it on,” Hoover says. “Around the world, people have disrespected salmon populations and their environments to the point where they are extinct or they are farmed. This place doesn’t have that—yet.”

Hoover maneuvers us into position. Two crewmen stand ready on the deck. One is a high school English teacher with a toddler at home, the other a high school student—a good kid who never gets tired. There isn’t room to mess this up. They have to make money this summer.

At 4:45 precisely, Hoover motors forward. Her net sails into the sea.”

Read the rest here.